Reference All Home

3 Weeks Until Launch.

Update #4

Points of Origin, The Structure of Vastland, and Graduate Degrees for a Half-Twist.

Circa 2007, I’m in a desert. Forward deployed, first combat tour. It’s eleven PM, the night before a big op. Somehow, I’m in a Hesco bunker standing in front of the squad leader responsible for mounted patrols. He’s explaining that one of his drivers had creative differences with the vehicle commander, so he now needs a replacement driver who won’t throw hands. A driver, but this isn’t just driving. Driving is what you do on a morning commute. Driving is what you do to go pick up groceries. Operating an up-armored Humvee to tactically insert a dismounted patrol into a confined urban setting is not the same thing: it is a specialist role requiring extensive training. When the squad leader was done explaining the situation, he didn’t ask me if I had experience, of which we both knew I had none, nor did he ask me for an opinion, of which we both knew he didn’t care. He simply asked if I had a Humvee license, to which I said no. And his response is something I still think about to this day. “Don’t worry, out here, it’s pass or fail.”

Nine hours later, I was punching a General Dynamics M1114 UAH along an alleyway so narrow it had stray dogs wall-climbing to get clear of us. Thick, heavy dust everywhere. We were operating blackout–no lights–and overdriving our infrared beams, which reduced my main source of feedback: my turret gunner screaming, “WALL, WALL, WALL” every time we got a little too close for comfort. If we were to map the range of typical human experiences, I’m guessing this would likely fall outside of that. Despite the circumstances, in the moment, I was overcome with a strange, zen-like focus; a state of mind largely dependent on another experience that had happened a few years prior.

The summer after I turned sixteen, my siblings and I were visiting my grandparents in Minnesota. We were taking the scenic route home from a weekend-long camping excursion when my Grandpa pulled over and tossed me the keys to his brand new F-150. My turn. I had a four-month-old driver’s license, a 1992 Ford Escort, and some experience bushhogging fencerows, none of which were the same thing as towing a 5th wheel camper behind a pickup, which also happened to contain my three younger siblings and grandma. One thing you need to understand about my grandpa is that he’s an engineer, who had us run math equations “for fun,” and probably the greatest safety adherent I’ve ever known. He’s also a wizard at helping people access their untapped potential, which in this instance, meant handing a $100,000 vehicle assembly over to his teenage grandson, along with this timeless bit of advice:

“Don’t worry, it’s pass or fail.”

Now you’re probably wondering what the hell this pair of anecdotes has to do with Vastland, so here it is: both narratives are defined by strange loops.

Every story has a shape to it. A structural form that uses tension, plot events, and character actions to chart a course toward the end. If narrative structures are something you haven’t thought much about, don’t worry: as humans, we naturally understand how to communicate information in ways others can appreciate. In fact, when done well, you shouldn’t even notice these structures at all. So why am I telling you all of this now, when you haven’t even seen the book? Simple. Foreshadowing. And as media theorist Marshall McLuhan put it, the medium is the message. Or, in the words of the person who handed me the courage to begin this book, a one Dr. Charles Kovitch, “the medium is the massage.”

Additionally, I like to think the structure of defining Vastland is somewhat unique, so as we take the scenic route to launch, I thought I’d give you a bit of behind-the-scenes for what’s coming down the line.

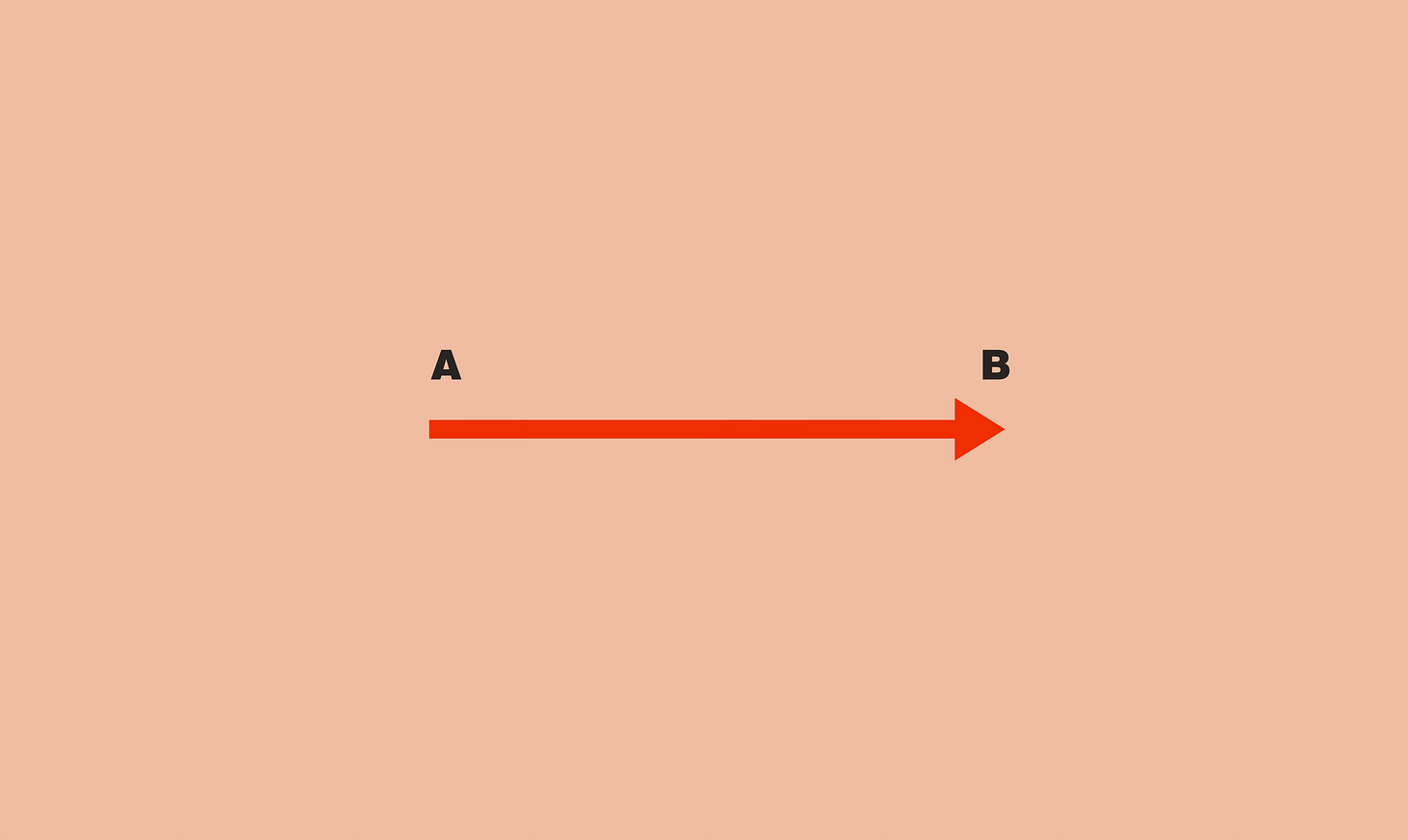

And a line is where we begin. The oldest and most basic of story shapes can be illustrated as a series of three points: the beginning, the end, and what happens in between.

A line is static, but a story is about progression. A character moving toward or away from something. If two points make a line, then two points and a direction make a vector, so we could also conceptualize this structure as movement along the X axis.

There is no shortage of writers who find ways to expand upon this form, dividing and subdividing the narrative into smaller sequences: Shakespeare, for example, was a well-known proponent of the five-act structure (introduction/rising action/climax/falling action/denouement). As this elemental story structure evolves, we also begin to observe movement not only along the X axis (forward/backward), but also along the Y axis (up/down), which are translated as positive or negative events for the story’s characters. Freytag's Pyramid is an example of one such evolution, which takes the five-act structure, establishes a baseline (0), and then defines events at key positions where the forward movement is also rising or falling. If the story is a tragedy, you might expect the character to finish below where they started in terms of value, whereas with a comedy, we would expect an ending above the baseline. And, perhaps my favorite of all, the transformation story, they end up right back at 0, changed in some internal way by the course of their journey.

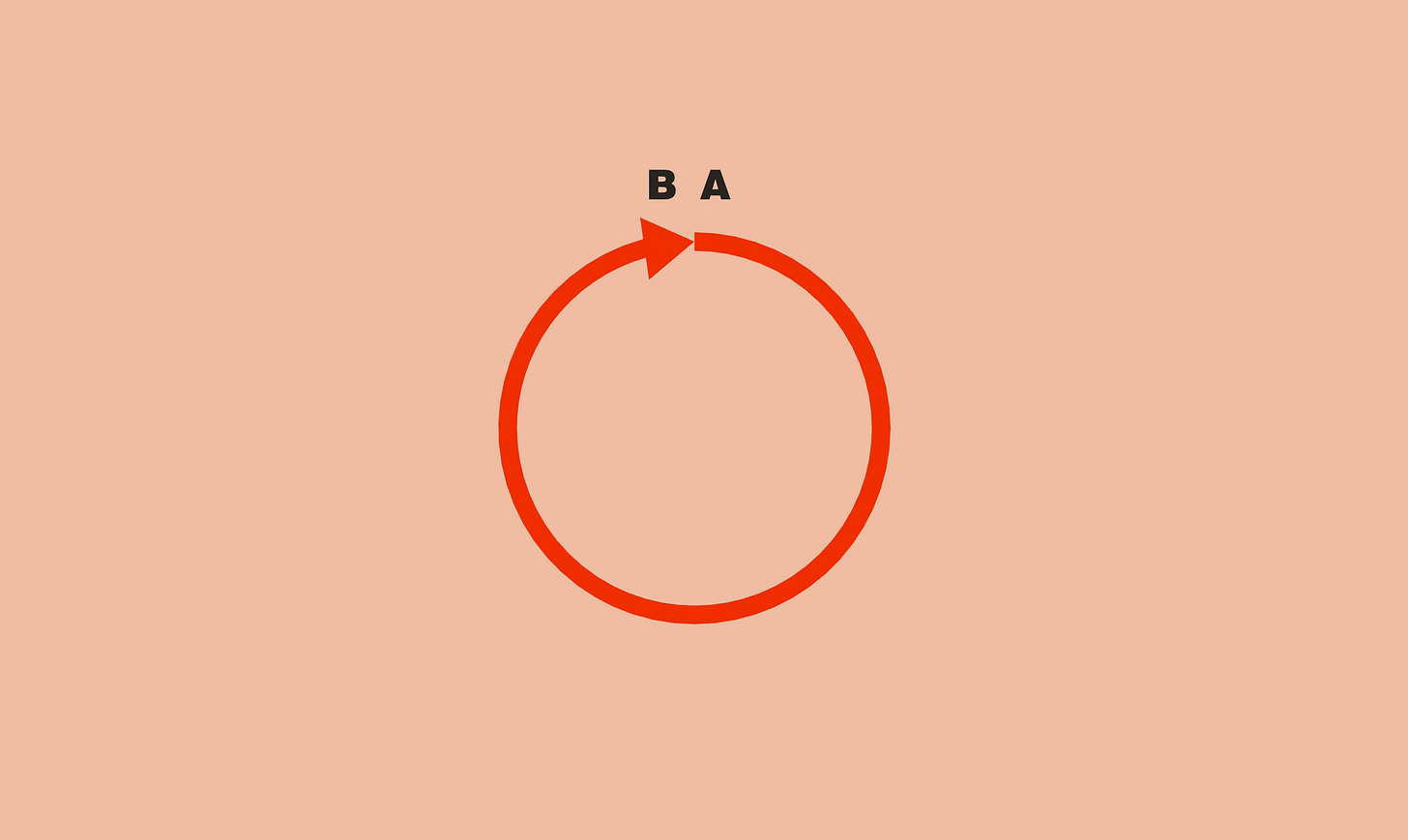

When the end of the story mirrors the beginning, a new story structure opens up, creating the opportunity for layered expressions of symbolism and meaning that extend beyond the physical place and circumstances of the start point.

If we return to our earlier line, we can visualize this by wrapping the end back around, which leaves us with the circular story shape.

Ah, a tale as old as time. A tale outside of time, even. Let’s look at a few of my favorites:

John Wick: a man gets a puppy, someone kills the puppy, the man picks up a Taran Tactical Combat Master Glock and goes center axis relock on an entire crime ring, the man gets a new puppy.

Lord of the Rings: Hobbits in the Shire, Hobbits fuck around and find out with a dark lord, Hobbits in the Shire.

The Odyssey: Odysseus at home is the man, Odysseus away from home loses all his men, Odysseus at home is a man.

I’m sure you saw this coming, but this also happens to be the narrative structure of Vastland, only with a half-twist.

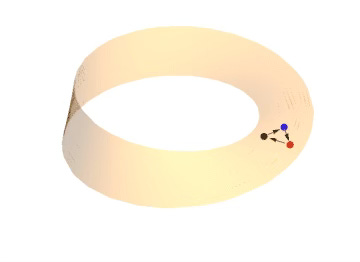

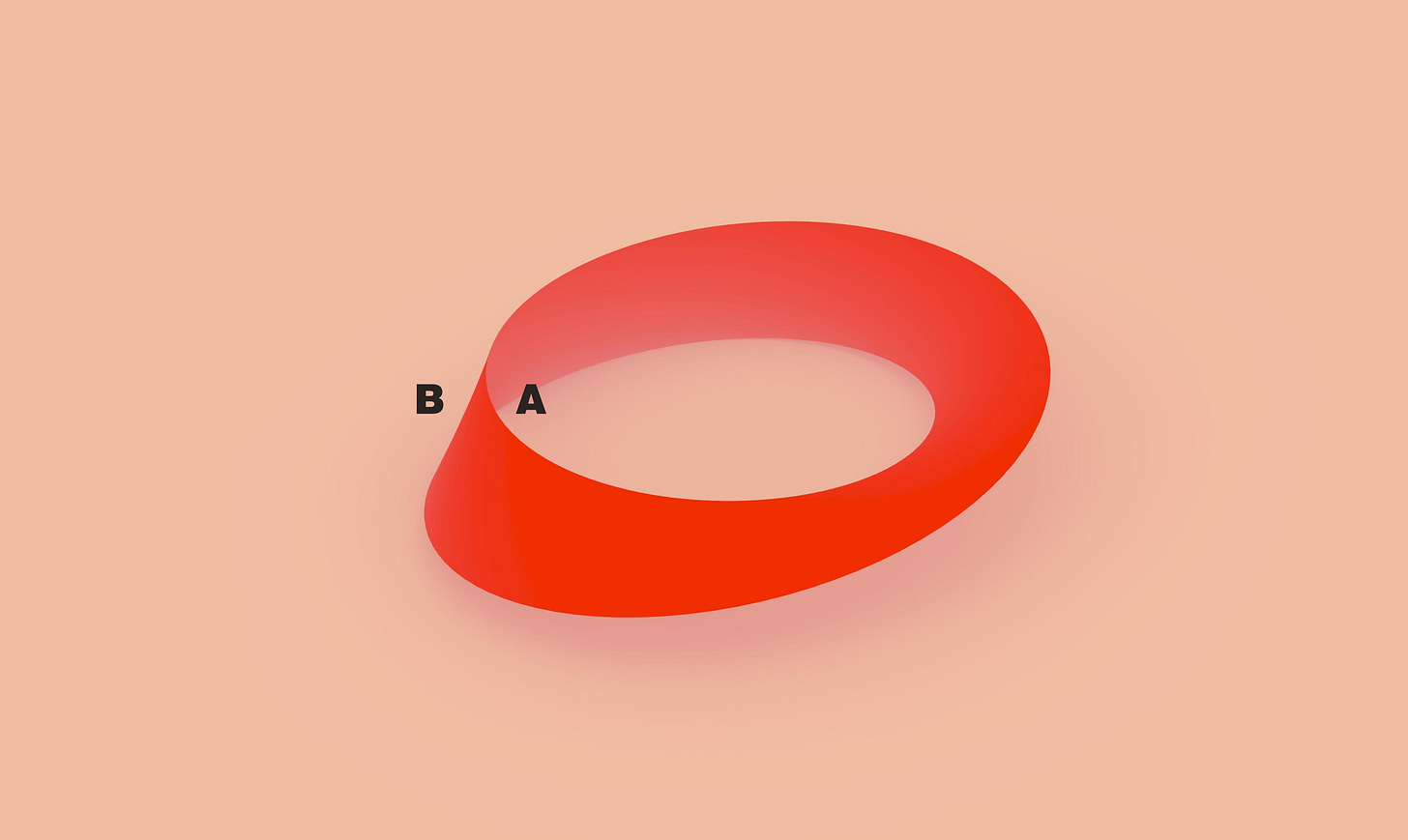

Enter the Möbius strip.

For those who are finding this a first introduction, the Möbius strip is a fascinating shape consisting of a single, three-dimensional surface with a half-fold, or twist, which also means it falls under the category of non-orientable shapes.

I’m a huge fan of shapes. Round, angular, asymmetrical, icosidodecahedral. In light of this disclosure, it should probably come as no surprise that I work in architecture. A field which allows me to, as a friend so succinctly described it, “fuck with shapes.”

Yes. Yes, we do.

It was around the beginning of grad school that the Möbius came to me. I was loosely aware of it, although it took another major milestone–the role of fabrication–in my own personal narrative structure to bring it to prominence. It’s in my nature to make, and studying architecture was more of a consolidation of many other skills into a focused career path. While my peers honed their professional skills and gained a working understanding of useful things like building codes and curtain wall systems, I was making loops. Möbius loops, to be specific.

There’s something incredible about taking a deep dive into a concept that you only vaguely understand and then noticing how the knowledge condenses, crystallizing into new structures with new relationships and meanings of their own. Like any good obsessive (and much to the dismay of my faculty), I found a way to shoehorn my favorite shape into everything I did, from building diagrams to light fixtures. It was excessive, illuminating, and helped me understand why I loved this form so much.

The Möbius Loop wasn’t just a shape; it was the shape of me.

I’ve found that certain things often find a way of coming back around, changed in some way, and yet still familiar. If you can learn to watch for these moments, there’s an incredible amount of understanding about yourself, your work, and that path you are on in life that comes with these observations. This insight became something of an operational philosophy for me over the last decade.

Janna Levin, a brilliant writer and cosmologist, has possibly the best description of this I’ve seen to date.1 She explains that when an object moves around a circle, it comes back as the same object. A right-handed glove that makes a full trip will always return a right-handed glove. Now take that same object and move it along a Möbius strip, and it will return the mirror image of itself. A transformation arc: the right-handed glove goes on a journey, and by some shapely magic, returns to where it began, left-handed.2

And so, we introduce movement in the Z direction. X as forward (or backward) movement, Y as up (positive) or down (negative), and Z, possible rotation which flips the character on their head or spinning out of control.

This has always resonated with me because, like the pair of experiences I shared earlier, life has always felt cyclical to me. It’s easy to slip into thinking about our existence as a linear path because we can’t step outside of the moment in which we exist. Take a step back, however, and you’ll begin to notice this circular structure everywhere. The seasons come and go, as do lunar events, the ocean tides, even life and death, which can feel like a giant carousel when understood beyond the linear experience of human consciousness. This also opens the door to take this idea one step further by considering the fourth dimension: time.

Without getting too deep into the tall grass, this phenomenon is apparent even on a surface level by phrases that we often use when feeling stuck, trapped, or at an end; ultimatums such as “this always happens to me” or “it never works out,” “here we go again,” and “this is the last time.” This shape appears as a tessellation in reality, manifesting in everything we do, from the structure of our sentences to that of the universe.3

Something else I love about the shape of the Möbius strip is that for every point you could select along it, there’s a corresponding point on the underside. The dark reflection, the shadow self. This is not a new idea. The ancient Greeks expressed this through the idea of the daemon, a guiding entity that was intended to help someone achieve their purpose. And for those who lost sight of this goal, the helpful daemon would become frustrated and take up the role of a domestic trickster, confusing and distorting the person out of spite for their failed ability to act. I think for anyone who has found something that resonates, this will ring true.

With this in mind, we can summarize the plot structure of Vastland with a fourth and final diagram:

Emélie, our main chracter, begins, and at some point, there is an ending which aligns with that beginning.

Or does it? Only one way to find out.

This is all essentially the scenic route to me saying that Vastland felt like something I needed to do, and the way I made it, and the structure of the thing, itself, are as much a part of the story as each line of text. I started writing in that very desert where this story opened, and I didn’t stop writing until I was done. Five years, ten years, fifteen. Didn’t matter. I wrote because I wanted to, and I have to say, there’s an immense joy in doing something because you love it. For me, that thing is writing. My oldest ritual, and it’s also the thing I do first and last. The thing I can’t help but do; what I return to when I’m grief-stricken, joy-drenched, tired, bored, excited, playful.

The reference point for all other positions of self.

As I wrote, the structure emerged, and then I wrote into it. A loop. I learned a lot about myself and my own life in the process. Most of all, things have a funny way of coming back around if you pay attention to them. There’s a well-known sentiment among authors that your first work is your most autobiographical. The thing you make because of some internal change and the desire to capture what existed before. A tombstone, of sorts. I certainly feel that. I am all of the characters. Some version of myself, or my other, frozen in a moment. And these are made and remade, hammering them out over and over until they feel true and alive.

This also means that, if taken to the conclusion, the part where B loops back around at A, you’ll end up with something so truthful it has the real chance of alienating a lot of potential audience. “Lacks commercial appeal.” Good. I’m not here for that. Pulitzer prize winning novelist Paul Harding said about writing with truthfulness that the moment you put down the first sentence, you can hear crowds of people stampeding for the door, but then some people also come down from the cheap seats to the front row and ask, ‘and then what?’ and those are the people for whom you write your book, beginning first, with yourself.

Learning to think of life in terms of strange loops also means there are new questions about the structure of your own story that may not have been visible at first glance:

What if I put myself through graduate school just to understand a single shape? What if the last ten years, where I wrote ten versions of the same book, had been better spent writing ten different books? Is this work too far into the underside of my own Möbius loop to make a public thing?

These are not questions with answers. These are points of reference, because I know no matter where I go, how far I move forward, positive or negative, twist or no, I will have this moment.

Reference all home origins: my own personal 0,0,0.

And you’re here, sharing it, because you want to. So, I’ll grab the keys and turn the story engine. All of you in the backseat; the rest is just pass or fail.

One more trip into the Loop. ⭕️

All these years later, I now discover that story was about the first time you operated the Humvee?! I love that story! I tell it to others because of how you spun it to me, yet the initial detail was omitted upon the premier telling! That makes it even better.

I meant to say this last week, but forgot to come back and leave a comment. Looks like I had to travel backwards a bit to fit it in. ⭕

The möbius strip has always been such a fascinating idea. Something that is explained mathematically in two dimensions can exist in a three dimensional space. Also the serpentine belt in a car is shaped like a möbius strip. So the analogy with driving a vehicle is very fitting.